musings in the beer aisle

2015-08-13

|~8 min read

|1421 words

Preamble

I love beer. Thanks in part to a stint in Prague and living with a beer nerd for a year, it’s a real treat to stand in front of a beer aisle and find a new beer to take home.

The fun ends as soon as I’m forced to make a choice. It’s when I’m faced with dozens, if not hundreds, of great options that my heart beats a little faster and the perspiration gathers on my temples.

This was the situation I found myself in last weekend when I was looking for a beer to pair with dinner.

|

|---|

| via SummitLiquor.com Evidently, the largest selection of craft beer in Saint Paul, MN (my home town). |

The market for beer

My first exposure to looking at the beer market was through a case study I did while at UW. The case has stuck with me (who’s surprised that I remember more about the beer industry than a similarly detailed look into the market for supertankers or aluminum production?).

|

|---|

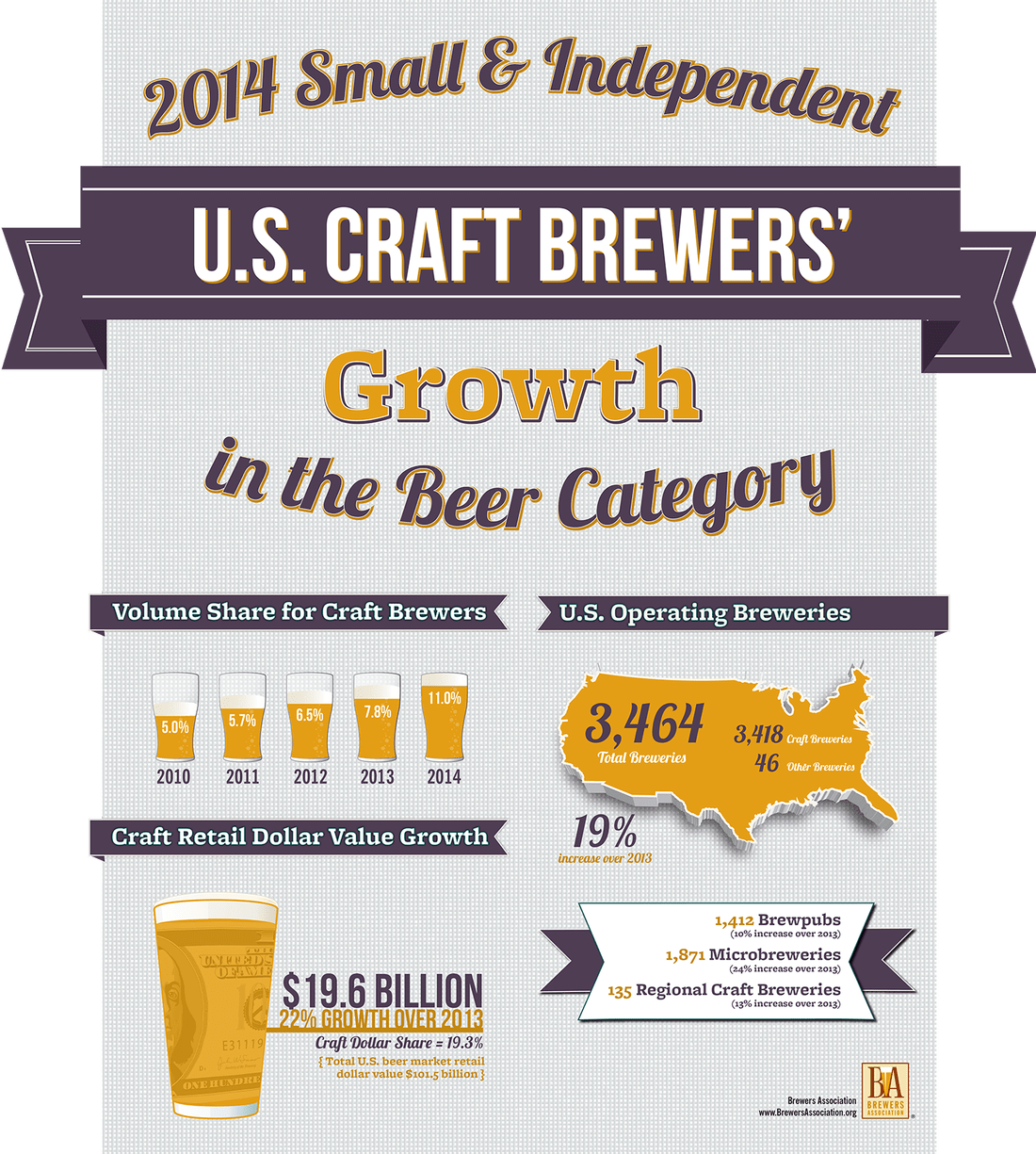

| via BrewersAssociation.org |

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the brewing industry experienced a massive consolidation, shrinking from more than 4,000 breweries at the end of the 18th century to fewer than 100 in 1980 (The American Brewery: A Portable History of Beer Making).

Brewing is an industry which benefits from economies of scale both on the input and output side. As a brewery grows, it is able to negotiate better prices for the raw materials that go into the beer (namely barley, hops, and water though other ingredients are now used as well) and gains leverage with distributors. The consolidation peaked in 1980 when the top 10 brewers produced an astounding 93% of all barrels.

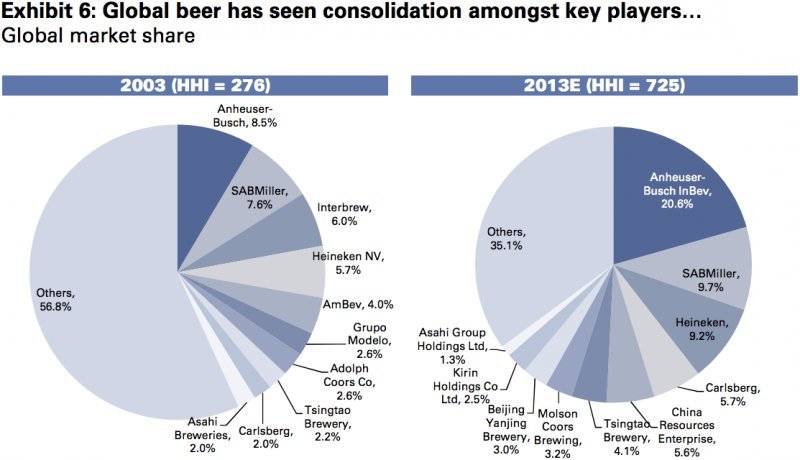

It was in this environment that we have witnessed the reemergence of microbreweries. (For those who would like more information, The Craft Beer Revolution comes highly recommended.) Last year, microbreweries claimed a 10%+ of the volume share with 3,400+ breweries in operation (a 100%+ increase since 2008), despite a resurgence in consolidation which has seen the top 5 companies increase their share from ~25% to 50%+ of the market.

|

|---|

| via BusinessInsider.com |

The dramatic increase in microbreweries is evidence of the demand for greater variety that was not met during the age of the American Lager. One of the most interesting lessons from the case was the rampant use of A/B testing beer recipes which yielded some of the most bland (and non-offending) recipes conceivable. The A/B testing conducted at the breweries would ask participants to compare samples of recipes and indicate a preference. The preferred recipe was then compared against a slightly varied recipe. The process was repeated until they arrived at a recipe that was preferred by the most people against the alternative.

When we try to please everyone, we end up pleasing no one…least of all, ourselves. – Simon Sinek

The process can make sense in theory. Iterate the recipe continuously until the market has declared their favorite. The issue, however, was in how the testing was conducted. Firstly, testers were asked only to give their opinions on the initial taste and not compelled to drink a full glass. This encouraged a pleasant front-end with no bite. Secondly, once the recipes were whittled down, the finalists were never compared to the discarded versions.

Imagine a world with 26 iterations of recipes in which each progressive recipe is preferred to the former. Then recipe A is compared to B and B is preferred. B is compared to C and C is preferred… Y is compared to Z and Z is preferred. Having exhausted our options, Z will now be the recipe that is put into production. While this is an efficient method for comparing different pairs (only 26 comparisons), it misses quite a few permutations (I wrote about this growth in a previous post here). Specifically, having never compared A to Z, we don’t know if we actually prefer Z to A, only that we prefer Z to Y (and Y to X, etc.).

The outcomes should be the same according to the transitive properties of inequality, however, given that tastes are multi-factorial, the preferences of B over A may depend on a different basket of features than the preference of C over B. As a result, it does not necessarily follow that C will be preferred over A.

Choosing a beer

So, there I was. Planted firmly in front of the beer fridge at the local Whole Foods, confronted with more options than I could process. I was paralyzed by choice.

I wasn’t just choosing for myself, a difficult enough task given the numerous options, but I also had to find one that Kate would enjoy. Since we tend to lean toward different styles and flavors – I prefer the dark and chewy, she likes the light and hoppy – finding an option for both of us can be difficult. More than anything though, I like the novel, which helps to pave the way toward a middle ground.

I started evaluating the beer in front of me across a number of criteria: style, flavors, reputation of the brewery, and price were the easiest to identify. It is a standard framework, but when I got to price, something interesting happened.

There was a beer on the shelf that sounded interesting – it was from a new brewery, it had a nice bouquet of summery notes that would pair well with our summer pasta salad, but it was only $4 for a bomber. Instead of thinking I had found a good deal, I steered clear of the beer. It felt like the equivalent of two buck chuck in the wine market and I was left with the (likely false) impression that the beer was well marketed but of sub-par quality.

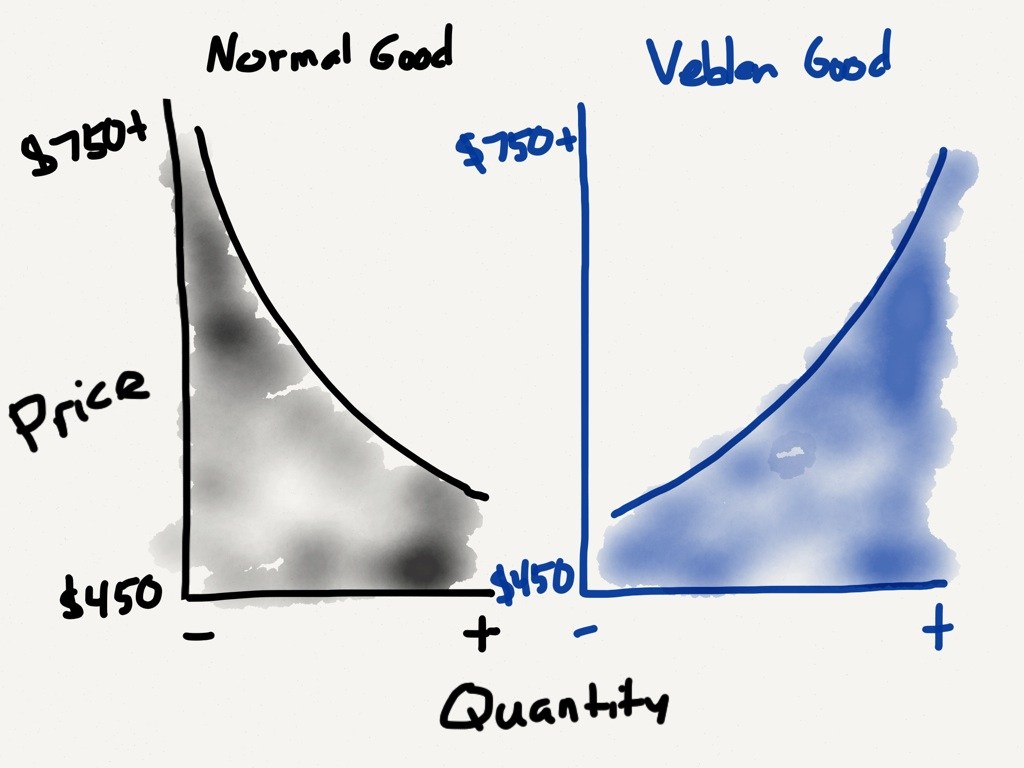

Veblen goods, formerly just a theory we’d discussed in class, were real. The higher the price of the beer, the more I wanted it. I was using the price of a beer as a marker for quality. These lessons certainly do not apply to all goods or markets; the fact is that when I’m confronted with too many choices, I look for shortcuts (and it seems reasonable that I’m not an outlier here). I don’t have the time, patience, of frameworks to process all of the variables, so I use heuristics and reviews to help guide my decision.

|

|---|

| via Stratechery.com |

After a few years, I’ve developed a pretty good understanding of which buzzwords correlate to beers I enjoy. I don’t recognize the varieties of hops, but I do notice when the notes are caramel vs. cocoa or piney vs peppery. However, since I’m frequently searching for a new experience, I’ll also rely on the bevy of information available from reviews. BeerAdvocate is one of my most trusted advisors in helping me to make decisions and I’ll review it several times in a single search.

For new breweries, the implications of my reaction to pricing can put them in a difficult position. The best way to establish their names are by getting more people to taste and review their product. One way to make this happen is to make it widely available to all consumers by lowering the price. However, this can backfire if potential customers avoid it.

So, how did the episode end? I found something new among the familiar. The reputations of some of my favorite breweries were able to convince me to take a chance on new recipes. I ended up placing three different beers from two of my favorite breweries into my cart before calling it a night: an Imperial IPA and Imperial Stout from Southern Tier, and a white IPA from Deschutes.

The IPAs were delicious and I’m looking forward to chewing on the stout shortly.

Further readings on choice For anyone who has been paralyzed by choice or is interested in learning more about how we can help ourselves make decisions better, two recommendations depending on the time you are looking to invest:

- Tim Ferriss’ short essay, “The Choice Minimal Lifestyle” (~5 minutes)

- Barry Schwartz’s The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less (~5-10 hours)

I remember the first time I heard Tim Ferriss reading his essay as a short “in-between-isode” for his podcast and frantically taking notes on my phone in the back of an Uber en route to dinner. That episode was actually what finally motivated me to pick up The Paradox of Choice which had been on my reading list for months.

Hi there and thanks for reading! My name's Stephen. I live in Chicago with my wife, Kate, and dog, Finn. Want more? See about and get in touch!