should education be subsidized?

2015-07-19

|~11 min read

|2039 words

Beyond my health, education is probably the single greatest gift I have ever received. I am eternally grateful to my parents, my teachers, and my peers for always pushing me further and encouraging me. It is important to recognize that learning is different than spending time in school. Good Will Hunting provides a wonderful launching point for this conversation on the merits of education.

“Yeah, but I will have a degree, and you’ll be serving my kids fries at a drive-thru on our way to a skiing trip.”1

Matt Damon makes a case that education is more than degrees. It’s thinking and connections - both with thoughts and with people. His public library education is impressive and demonstrates how truly gifted his character, Will Hunting, is. The grad student, however, parries and implies that it does not matter if he is not as educated, he possesses something of greater value - a prestigious degree affording him a life of comfort.

Candidates for subsidization

In order to answer the question of whether we should or should not subsidize education, we must first answer two questions:

- Does education have an externality?

- Is it positive or negative?

Externalities are simply benefits accrued by someone who is not part of the transaction. One example of a positive externality is the protection afforded to non-_vaccinated individuals in a community that is highly vaccinated, this is commonly referred to as “Herd Immunity.”2 We have three possible outcomes then. If there is _no externality, then the case for any intervention should be challenged. If a positive externality exists, education should be subsidized. If a negative externality exists, education would be taxable.

Arguments for an externality

Arnold Kling, in his post on EconLog.org, “Public Goods, Externalities, and Education” succinctly summarizes how one might argue for an externality of education, albeit in a rather skeptical fashion:

“For education, the positive externality is the benefits that accrue to me from your education. I think that those benefits tend to be pretty small. You get a higher income, and most of those benefits flow to you. I get some of the benefits, because you are more likely to pay taxes and less likely to require government transfers, so that my tax obligations can be correspondingly reduced.”3

Continuing later with a discussion about potential social costs accrued due to signaling, Kling is arguing that while it seems clear education possesses externality, the direction of the externalities is less certain. The question will therefore be, whether the net is positive or negative and whether education should be subsidized or taxed.

Arguments for positive externality

Arguments for the positive externalities of education are centuries old, but tend to focus on how an educated society can be more just, democratic, and productive. For more on this, I recommend reading Julia Pointer Puntam’s “Another Education is Happening” a contemporary example from Detroit founded in classic educational thought. This quote from a Times Higher Education article on the merits of education seems to sum up many of the arguments regarding the benefits of education to society:

The new report presents evidence that higher education participation improves social cohesion, social mobility, social capital and political stability. Wider non-market benefits to individuals highlighted include a populace more likely to vote, longer life expectancy, greater life satisfaction, better general health and lower incidence of obesity. Economic benefits to society include increased tax revenues, faster economic growth, greater innovation and labour market flexibility, while individuals profit from higher earnings, lower unemployment and higher productivity.4

Further, in their report, A Well-Educated Workforce Is Key to State Prosperity, authors Noah Berger and Peter Fisher write for the Economic Policy Institute argue that one of the best ways for a state to “build a strong foundation for economic success and shared prosperity” is by investing in education.5

Arguments for negative externality

The foundation of an argument about the negative externality of education really lies in education as a signal. On his blog, Mapping Ignorance, José Luis Ferreira, an associate professor of economics helps to explain how education could be used as a signal by Michael Spence’s paper, “Job Market Signaling.”

Spence notes that if own (sic) ability is known by the employee but not by the employer, and the cost of getting educated is greater for employees with lower abilities, then an equilibrium may exist in which employees acquire education only to signal that they are of high ability. Less able employees do not get the education because for them is too costly, and the higher salary in case they are treated as high ability workers does not compensate. If this is the case, employers can safely assume that educated employers are indeed the ones with high ability, thus completing the conditions for the situation to be an equilibrium.6

Said another way - the abilities of someone with a degree and someone without are different; however, it does not follow that that difference is due to the time in school earning a degree but may in fact be due to differences in ability unrelated to the degree. In “Everyone benefits from an educated citizenry”, JP Foley writes,

The first benefit [of a college degree] is the competitive advantage. According to the 2000 Census, only 22 percent of New Mexico’s adults have a college degree. Therefore, completing a degree places the student in that 22 percent of the job-seeking population, versus the other 78 percent.7

This is the signaling story. While Mr. Foley elaborates later in the piece on how education benefits the community as a whole, it is telling that the first benefit named is that having a college degree automatically places the recipient in a smaller pool. How does signaling create a negative externality? For every additional year of education that I attain, I make it more difficult for someone who is smarter to differentiate his/herself. By going to school for more education, I impose a cost on my neighbor who must now also get another year of education to maintain his/her distinction, fueling an arms race amongst candidates.

Conclusion: It’s all about the magnitudes

The question of whether or not education has externalities seems to be well established on both sides. Social costs, positive and negative, are outlined above. In order to determine whether or not education should be subsidized, it is a question of which effect is larger. That will be a question for another time.

Appendix

The return to an education subsidy

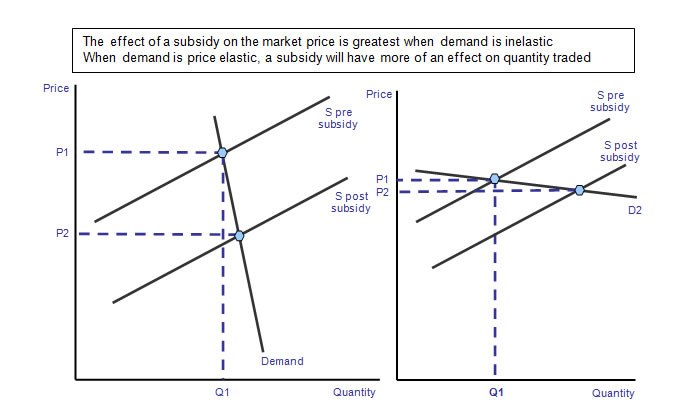

The return on a subsidy is determined by the elasticity of the supply or the demand curve. When it comes to education, rising tuition costs are not offset by equal decreases in demand. The Center for College Affordability and Productivity cites findings from Dave Narcotte and Steven Hemelt who estimate “overall the elasticity of demand [for higher education] is -.10 --- a 10 percent increase in tuition fees will lower the quantity demanded be one percent.”8 Due to the inelasticity in demand of education, the amount of money to attain the same increase in supply will be larger than if education had a flatter, more elastic, curve.

|

|---|

| On the left, is an inelastic demand curve. To move from Q1 to the new equilibrium at P2, requires a subsidy on the magnitude of the difference between supply pre-subsidy and supply post subsidy. On the right, you can see how the story changes in terms of additional supply when the demand is elastic.9 |

Education versus years of schooling

It’s worth noting that any subsidy of education cannot be directly applied to the good education. Due to variations among teachers and the lack of visibility into which teachers are effective, any subsidies of education are actually for years of schooling, a proxy at best.

Subsidies and Elasticity: A look at the economics

Generically, subsidies are cash transfers to a supplier to encourage production of a good. Typically, these transfers come from governments or employers to encourage goods considered advantageous to the public or employees.10 The extent of a subsidy’s effect will be determined by the elasticity of both the supply and demand curves by affecting the new equilibrium.

In the public space, a subsidy is a mechanism way for a government to encourage more of something that benefits society at large. To fund subsidies a government would rely on taxation typically, while a private employer would decrease profits to provide the benefit it deems beneficial.

The degree to which these funds shift the equilibrium is determined by the degree to which both the supplier and the consumer respond to price changes, which is called elasticity.11 In understanding elastic vs. inelastic – I have always found the extremes helpful.

A perfectly elastic demand for a good is the case of a perfectly substitutable commodity. If a producer increases the price of a perfectly elastic commodity, the consumers will find a new supplier and demand falls to zero. If, on the other hand, the consumer hand lowered the price, the supplier will attract every consumer in the market and demand will increase to infinity.

Inelastic demand curves are the inverse. These are goods which you cannot live without and for which there are no substitutes. No matter the cost, you will continue to pay and as such a consumer has the ability to raise prices to infinity.12

So, what does this mean for subsidies?

If the demand curve is relatively elastic, a subsidy has the potential to increase the equilibrium quantity quite a bit. However, the opposite is also true when describing inelastic demand curves.

If the supply curve is relatively elastic, a small subsidy will increase the supply more than if it is inelastic. In an elastic environment, the size of the subsidy then, or the cost to the government, would be smaller to achieve the same shift as in an inelastic environment.

|

|---|

| I liked this graph for demonstrating the cost of the increase in quantity by calling out the size of the subsidy required to achieve the change.13 |

Sources

- 1 Good Will Hunting

- 2 Vaccines.gov – Community Immunity

- 3 Arnold Kling – Public Goods, Externalities, and Education

- 4 Times Higher Education – Higher education: It’s good for you (and society)

- 5 Economic Policy Institute – A Well-Educated Workforce Is Key to State Prosperity

- 6 Mapping Ignorance – Evidence of education as a signal

- 7 JP Foley – Everyone benefits from an educated citizenry

- 8 Center for College Affordability and Productivity – The elasticity of demand and student access

- 9 Econs.com – Market Failure

- 10 Wisebrain.Info – Use a diagram to explain how producers and consumers might benefit from a government subsidy to an industry

- 11 Wikipedia – Elasticity of Demand

- 12 Amos Web – Perfectly Elastic

- 13 Bized.Co – Subsidy of a good

Further reading

-

EconTalk – Bryan Caplan on College, Signaling, and Human Capital

- The inspiration for today’s, at the end of the interview Russ and Bryan discuss the arms race created by signaling education.

-

Bryan Caplan – Mixed signals

-

Right Brained Math – Furthering education: Signal or human capital?

- Brandon over at Right Brained Math had the same idea when listening to Russ and Bryan talk on EconTalk leading him to write this piece. It’s a good read.

-

Eric A. Hanushek – Valuing teachers: How much is a good teacher worth?

-

Jim Kjelland – Economic returns to higher education: Signaling v. human capital theory an analysis of competing theories

-

Center for Public Education – Teach quality and student achievement: Research review

-

Julia Pointer Putnam – Another education is happening

-

Insight News – Pushing children out of school—A new American value?

-

Michael Spence – Job Market Signaling

-

Helen Li – The Rising Cost of Higher Education: A Supply and Demand Analysis

-

Noahpinion Blog – College is Mostly About Human Capital.

-

TechCrunch – Productivity and the Education Delusion

-

Society for US Intellectual History – What good is education to society?

-

Julia Pointer Putnam – Another education is happening

Hi there and thanks for reading! My name's Stephen. I live in Chicago with my wife, Kate, and dog, Finn. Want more? See about and get in touch!