the purposeful pause practice

2019-04-23

|~6 min read

|1043 words

The world is busier than it used to be. We’re bombarded by constantly with work emails, Instagram notifications, and Slack messages. My solution, in so far as it is one, has been to delete the apps from my phone. But that works for only so long. Eventually, we need a break.

Breaks, not surprisingly, have been a solution to overwork and stress for hundreds of years. Cal Newport writes about Carl Jung’s escape to a summer cottage and Abraham Lincoln’s nightly rides to his house outside of DC. Teachers take sabbaticals (and more of us should).

Breaks don’t need to be days or weeks long. And they don’t need to take place in some foreign or exotic location. They just need to give us space to think. We can accomplish this by going for a walk through a park, or, even more simply, pausing purposefully and observing our surroundings, emotions, and planning the next course of action dispassionately.

Interestingly, I have found the five-minute interval between Pomodoro sessions to provide a convenient venue for this type of reflection. As a planned “do nothing” period (except to stretch or grab water), my brain gets to digest everything that’s going on without also having to process new information.

Sometimes there isn’t a break in the action though - such as when things are “happening to you.” These are situations like when your boss says something that upsets you, your colleague annoys you, or your spouse/partner disappoints you. In the heat of the moment, your body is the first responder and your face flushes, stomach clenches, hands sweat.

Without a pause button for life, we need a strategy for what to do in these moments so that we respond in a way that will make us proud in retrospect. After all, we’ve evolved to respond to stressful situations - quite effectively I may add. When we feel threatened or attacked, our fight/flight responses kick in and we can lash out. This is true even with people we love and admire. It’s not about them. Not at that moment. It’s about our emotions taking over and our minds responding automatically to a threatening feeling. Even though it’s automatic, that doesn’t mean that we don’t sometimes look back on how we acted with regret.

The question, then, is how do we still allow ourselves to be present to enjoy everything that life has to offer without lashing out when we wouldn’t want to with hindsight?

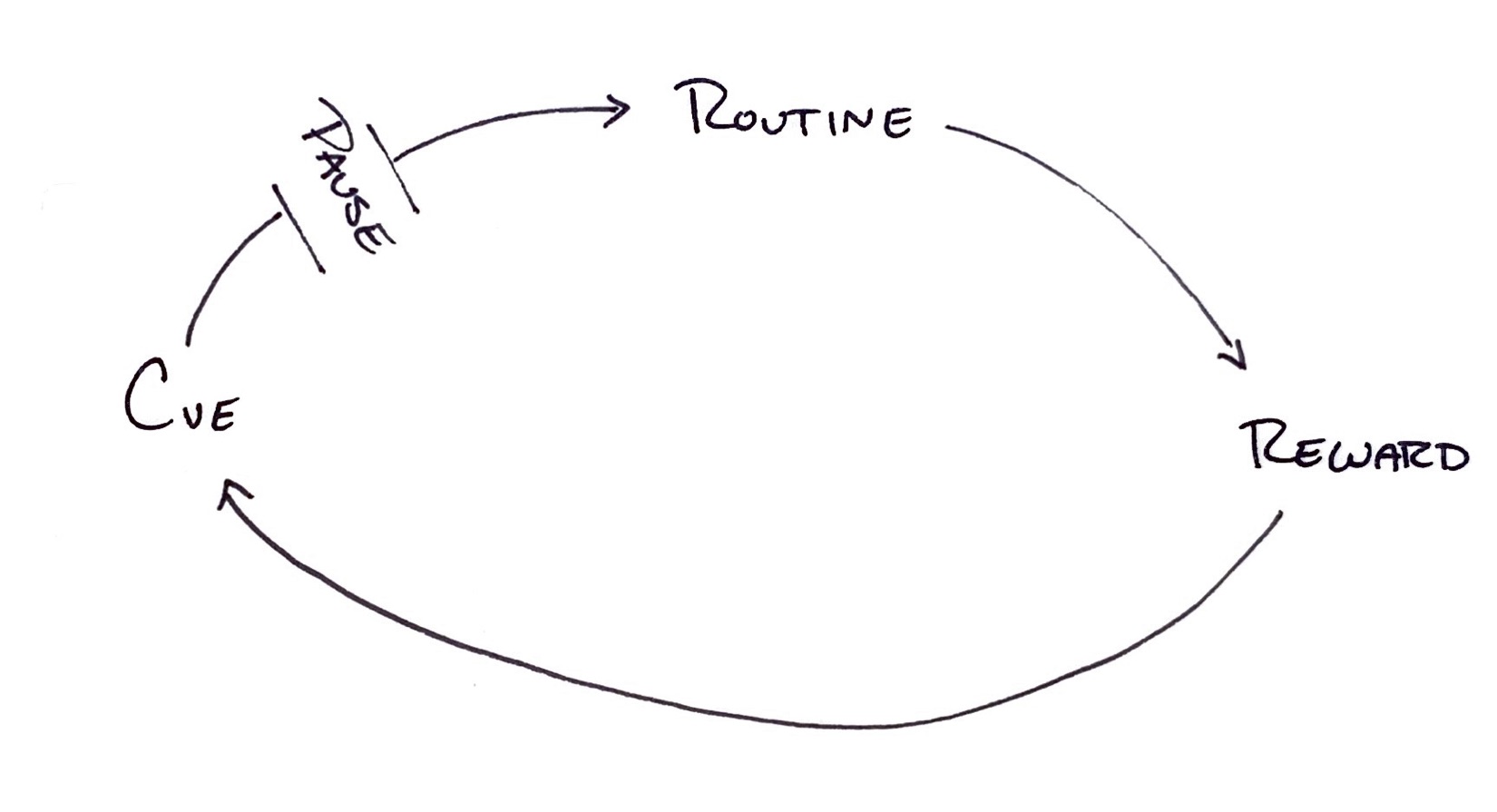

Last week, my friend, Jessica Dixon, gave a talk on a Purposeful Pause Practice, and I think the practice provides an answer. The key to its success is where the pause happens. It comes after the emotional and physiological response (we aren’t suppressing any emotions) but before acting on it. In trying to visualize this, I though of Charles Duhigg and the chart he drew to describe habits, which I’ve adapted below to include the pause.

The reason this ends up being such an effective pathway for habit formation is the plasticity of our brains and the mechanisms by which neural pathways form. Colloquially, we can describe this as “what fires together, wires together.” Barbara Oakley, who teaches a fantastic free course called Learning How To Learn, described it as the tire tracks left by a tractor. Being from Minnesota, it’s easier for me to envision them as the tracks in the snow from cars.

The first car who drives on a road following a snow storm can go anywhere. It’s a blank slate. The second car that comes behind, however, is much more likely to follow in the path of the first car — it’s just easier. This cycle continues until the choice of deviating outside of the established path is a significant one.

At the risk of torturing this analogy too much, two additional points:

- Deviating from the established path without slowing down is dangerous

- The first person likely wasn’t thinking about the optimal path for the future — they were just responding to the immediate situation to accomplish the task at hand - get from A to B. It’s only with the benefit of hindsight that we can evaluate the “rightness” of that decision.

Living intentionally, and by that I simply mean acting with intention, necessitates pausing. By thinking about whether the first response that comes to mind is the right one, let alone a good one, you improve your chances of making a decision you’ll be happy with later. The purposeful pause creates the space to ask this question by injecting space between the Cue and the Routine.

It doesn’t need to be much - it just needs to slow you down enough that if you decide to deviate from the established / automatic response, you can do so safely.

What does it even mean to pause? What does it look like? It’s self-talk. In that moment after your body has responded to what’s going on with a flushed face, clenched stomach, or sweaty palms and before your brain really knows what’s happening, you acknowledge the feeling. In describing a moment of anxiety, Jessica described her inner monologue in the following way: “Hello anxiety, nice to see you, come in and have some tea.”

This naming of your emotions gives you power over them. It resembles the safety procedure, pointing-and-calling, popular in Japan, in which you both point and call out the name of what you’re observing. By drawing your attention and forcing your hands and mouth to engage, you create awareness of what you’re looking at. In terms of industrial settings, this can reduce risk of accident, but when it comes to our anxious thoughts, it neutralizes them by preventing your thoughts from running away from you.

This slowing down acts like pumping the breaks when you’re driving in the snow. You create new options by driving slowly. You can continue along the pre-worn path easily or exit. The choice is yours. And that is the fascinating feature of the purposeful pause practice. By pausing when you feel your emotions rising, you create opportunities to change your behavior in the present - and the future - through the rewiring of your brain. That feels like a strong case for pausing.

Resources

Hi there and thanks for reading! My name's Stephen. I live in Chicago with my wife, Kate, and dog, Finn. Want more? See about and get in touch!