who would buy a car programmed to sacrifice the owner?

2015-11-02

|~7 min read

|1384 words

“Who would buy a car programmed to sacrifice the owner?” 1

What I love about this question is that it gets at two conflicting priorities - situations in which it might make sense to kill a consumer and determining the demand for such a product.

The initial research on the subject which the article summarizes indicates that people prefer to have a car embedded with a utilitarian approach… except when they’re the ones in the car (I would say they’re the ones driving, but that’s the point - they’re no longer the drivers).

It might appear that the self-driving car is divorcing the driver from the car in the ethical decision of what when a crash is imminent. However, really what’s happening is the person we normally think of as the driver is now occupying the role of the passenger while the “driver” can be thousands of miles away and is the programer who determined the car’s approach to the situation. In a separate article, also on how self-driving cars make ethical decisions 2, one commenter concluded, “The car should always take the occupants safety as the primary goal.” A summary of the argument is included and goes as follows (emphasis is my own),

tl;dr morals: self defense is justifiable, the car represents the drivers will. Law: walking in front of an auto makes your death your own fault. Being tied or pushed in front of an auto makes your death the perpetrators fault. Practicality: If people are going to actually use these cars, they need to feel safe using them. It shouldn’t be possible for someone to jump in front of your auto in order to make your car kill you.

The argument feels extreme. Even today, driver’s don’t always “take the occupants [sic] safety as the primary goal.” If that were the case, we wouldn’t swerve for cats today. None-the-less, her final point seems spot on. Before addressing what self-driving cars should or shouldn’t do, I wanted to see where we are today. Cars are already helping drivers identify hazards 3, pedestrians they weren’t expecting 4> and cars in their blind spots 5. With that in mind, a discussion of ethics should be in the realms beyond these already addressed arenas. This is where our poster’s final point, comes in. Cars are already helping us detect hazards, but what happens when they are so last second that even the technology can’t stop the car, but does have the ability to affect the outcome, i.e. swerve.

Even humans, in this situation, do not respond predictably. Some will swerve in an effort to avoid the obstacle as in the case of the cat above while others will not. It is not immediately clear if those who swerve believe they will simply avoid the obstacle without risking their safety or swerve despite the increased risk to self. I would also question whether that is ever a knowable question - even for a computer. One of the underlying assumptions in the discussing the ethics of the self-driving car is that there is a knowable outcome and, working backwards, a right answer.

If there is a knowable outcome, then it seems likely a consumer would not willingly purchase a car she believed will sacrifice her for the safety of others. Even if a manufacturer attempted to be transparent, it seems unlikely that a consumer would ever get the nuanced approach used to determine the appropriate course of actions. Instead, that nuanced approach would get simplified into a soundbite and a headline - like ‘Death Panels’ of the Affordable Care Act legislation (a feature, by the way that was never included but became the focus of conversation through a misrepresentation of the law). 6

Equally at fault for the failure of making such a car an attractive product for consumers is our inability to objectively asses risk. The probability of dying in a terrorist attack are infinitesimal compared to a lightning strike or in a plane compared to a car crash. 7, 8 It comes down to how we perceive risk vs. the actual likelihood of the risk.9 Even though autonomous cars would dramatically reduce overall accidents, injuries, and car-related fatalities, because the risks are beyond our control, are in the future, and unknown, they loom large. Which brings me to whether drivers aught to feel safe while driving. It seems this wasn’t always the case. A time existed when kids were encouraged to play in the streets. It was a time before cars. As the team at 99% Invisible reports in their episode, “The Modern Moloch”, 1⁰

And then the automobile happened. And then automobiles began killing thousands of children, every year. Much of the public viewed the car as a death machine.

One newspaper cartoon even compared the car to Moloch, the god to whom the Ammonites supposedly sacrificed their children. Pedestrian deaths were considered public tragedies. Cities held parades and built monuments in memory of children who had been struck and killed by cars. Mothers of children killed in the streets were given a special white star to honor their loss.

And later (emphasis my own),

If a car hit someone, the car was to blame. From the New York Times, November 23, 1924:

‘The horrors of peace appear to be appalling than the horrors of war. The automobile looms up as a far more destructive piece of mechanism than the machine gun. The reckless motorist deals more death the artilleryman. The man in streets seems less safe than the man in the trench. The greatest single lethal factor is the automobile. It left shambles in its wake as it coursed through 1923.’

|

|---|

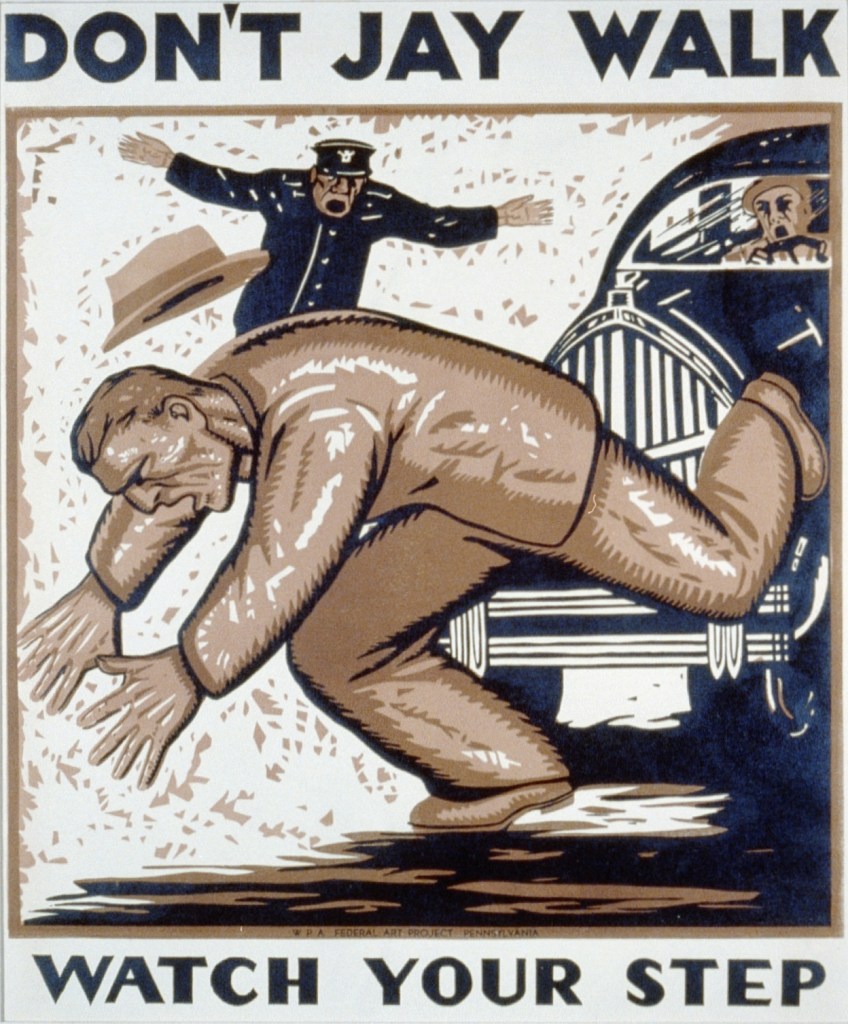

| Works Progress Administration/Federal Art Poster illustrated by Isadore Posoff, 1937 |

But drivers couldn’t be abated and the automobile companies formed an organization, Motordom, (how’s that for an awesome name) to help transform roads into a place for cars, not people. Early attempts were unsuccessful, but when they engaged in a public ridicule campaign by re-appropriating the term jaywalker from a merely annoying pedestrian to one who crosses the street at their leisure, they hit upon a winning strategy. (Jump to 14:13 for my favorite part of the episode.)

Will the introduction of self-driving cars return to a world where the car is at fault as it was when they were first introduced, when streets were for pedestrians? Or will they remain the domain of the automobile? Of course, this is not a complete set of options and other, unknown options may yet exist. Perhaps self-driving cars will be relegated to roads underground and pedestrians will have full reign of the land. Or they only travel on specially designated roads at high speeds and don’t travel more than 10 mph in pedestrian friendly zones.

No matter what, I think the effort to get more self-driving cars on the road is the right one. They will offer so many benefits, both foreseeable and not. And as someone who no longer drives and so doesn’t need a parking spot, reducing the demand for cars and allowing that energy and space to be used for other productive purposes seems like a glorious outcome. An outcome I am excited to see.

Footnotes

1 Why Self-Driving Cars Must Be Programmed to Kill | MIT Technology Review referencing ”Autonomous Vehicles Need Experimental Ethics: Are We Ready for Utilitarian Cars? | Cornell 2 How to Help Self-Driving Cars Make Ethical Decisions | MIT Technology Review” and How To Help Self Driving Cars Make Ethical Decisions | MIT Technology Review 3 ATTENTION ASSIST Vehicle Safety Technology — Mercedes Benz 2013 ML-Class | YouTube 4 Ford and Honda stop collisions before they happen with pedestrian detection | Extreme Tech 5 Infiniti’s Blind Spot Intervention System | Infiniti USA 6 Death Panels | Wikipedia” 7 Why Terrorism Is More Frightening Than Lightning | National Review 8 Think air travel is risky? Try driving a car | AutoBlog 9 Perceived Risk vs. Actual Risk | Bruce Schneier 10 The Modern Moloch | 99% Invisible 11 Detects dangers before they come up” – YouTube. While looking for information about hazard detection technology currently on the road, I found this spoof on Mercedes’ technology and detecting problems before they come up.

Hi there and thanks for reading! My name's Stephen. I live in Chicago with my wife, Kate, and dog, Finn. Want more? See about and get in touch!